Ragù alla Bolognese has become one of the preeminent symbols of Italian cuisine. When people ask me where I am from, I often respond, “I am from Ravenna, near Bologna, the city where ragù alla Bolognese originated.” In fact, ragù alla Bolognese is more than a recipe — it is like a megaphone that announces Bolognese cuisine to the world.

Talking About This Recipe Is Always Risky — Especially on Social Media

Ragù is a bit like carbonara: bring it up, and you are bound to offend some gastro-purists (especially online). Not long ago, I was watching a video on Instagram by a well-known American food writer who claimed he had learned how to cook the real ragù alla Bolognese. During the video, (i) the author blended the meat in a food processor; (ii) he skipped the Maillard reaction entirely; and (iii) he used only beef in the recipe. The comments ranged from outrage to amazement. Why such a strong reaction? Two hypotheses: (1) A good ragù is divinely delicious. (2) Tradition.

Here I provide a brief overview of the evolution of ragù alla Bolognese. I draw from a variety of sources some of which are cited below. You can find the full list at the end of this article.

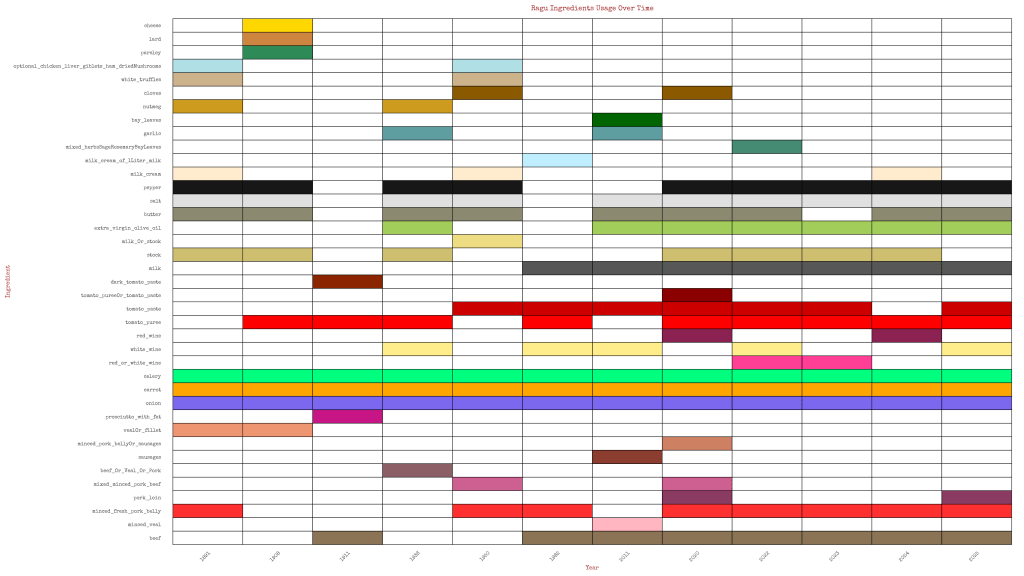

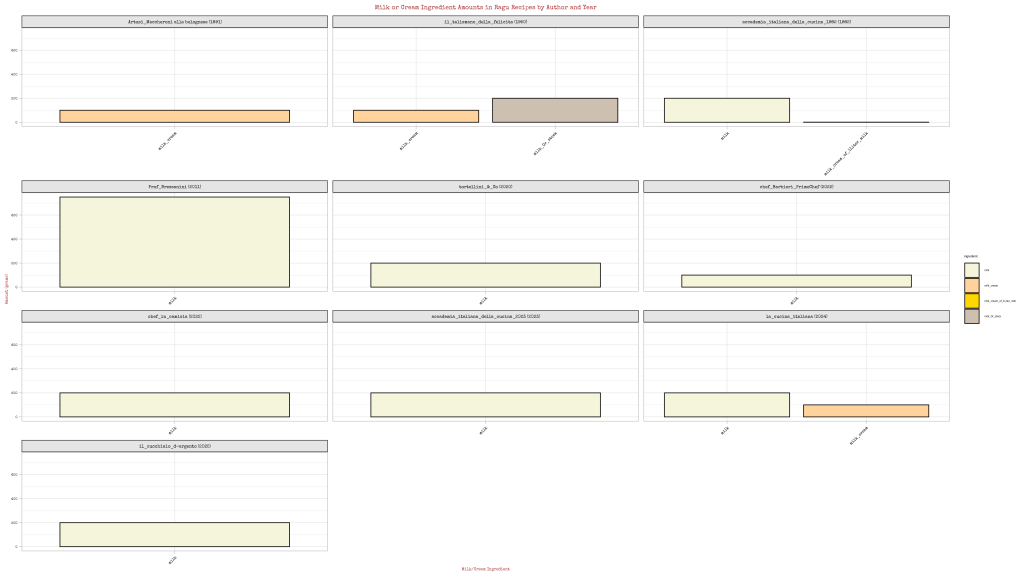

If you take a close look at the bar chart below — with ingredients listed on the left and the year of the recipe on the right — you’ll see when the ingredients appreared in those recipes.

Click on the image to zoom in and zoom out.

Has Ragù alla Bolognese Always Been Made This Way?

Short answer: No.

The long answer is laid out by journalist and food historian Luca Cesari in his book The History of Pasta in Ten Dishes, where he dedicates an entire chapter to ragù alla Bolognese (and another chapter to Neapolitan ragù). The recipe has changed many times over the years, and it hasn’t always had the same name or the same ingredients.

“While the earliest roots of ragù lie in French cuisine, unlike its Neapolitan cousin, it’s quite tricky to trace the first steps of the Bolognese version — at least until the publication of Pellegrino Artusi’s cookbook” (Cesari, p. 138).

AND ASIDE: DID YOU KNOW? The word ragù comes from the French ragoût — a thick sauce used to add flavor to otherwise insipid boiled meat or fish dishes. Originally, ragù wasn’t paired with pasta at all; it referred more broadly to a style of cooking and could be served alone (Cesari, p. 120)

When Did Tomatoes Make Their Way into Ragù alla Bolognese?

At first, ragù was what we Italians call in bianco, since it was cooked in broth and without tomatoes. The first appearance of tomatoes in a ragù-like recipe comes from Naples, in 1807, when Francesco Leonardi published the recipe in the second edition of his recipe book “Apicio Moderno”. But the Neapolitan version involved cooking whole chunks of meat, not minced meat (Cesari, p. 128).

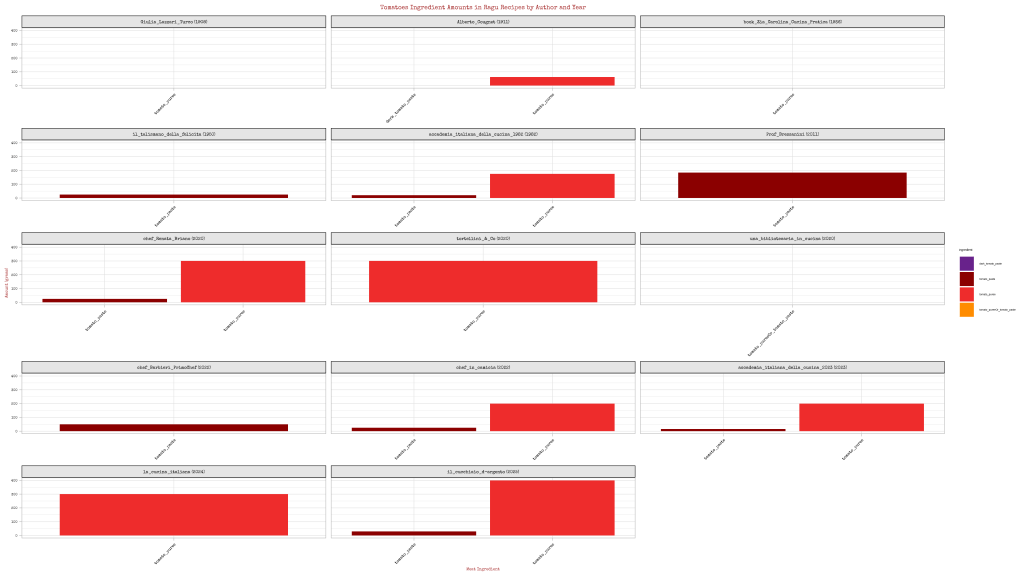

It wasn’t until 1908 that we find the first proper “Bolognese-style” version with both tomato sauce and minced meat, thanks to Giulia Lazzari-Turco. Still, her recipe included no pork, and she didn’t specify how much tomato to use.

(See Pasta alla bolognese, Turco, 1908).

Click on the image to zoom in and zoom out.

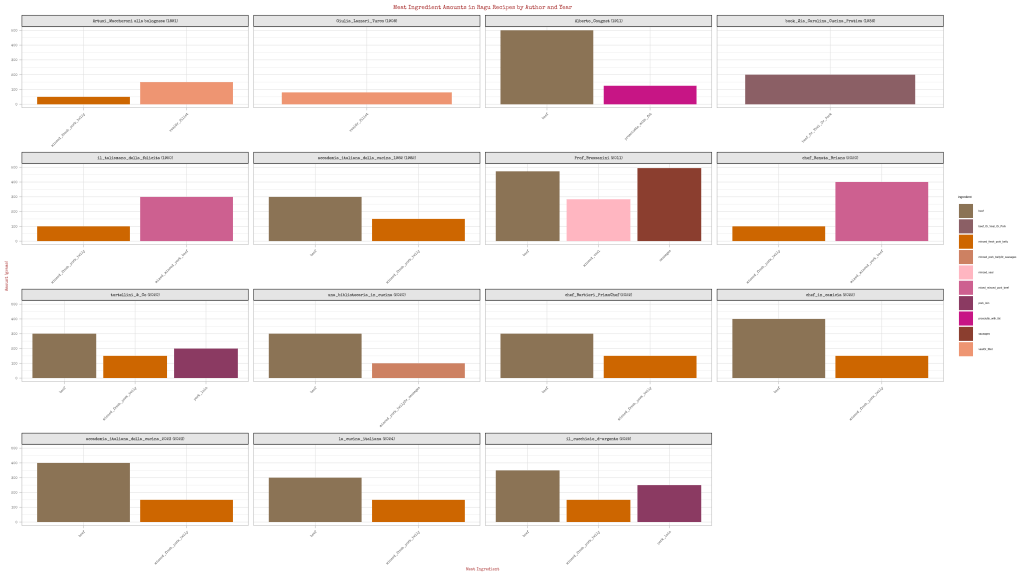

The Evolution of Meats Used in Ragù alla Bolognese (1891–Today)

The earliest experiments with ragù did not feature only beef. Poultry, game, and even sturgeon were used. Pork was introduced later, at first in small amounts — a bit of sausage here, a slice of pancetta there — until it became more common in the 20th century. Then, in 1950, Ada Boni published her famous cookbook Il talismano della felicità. Her version of ragù included pancetta, pork fat, and also tomato concentrate.

Pellegrino Artusi was the first to introduce pancetta (which he referred to as carnesecca). His cookbooks were published in fourteen editions between 1891 and 1911.

In 1911, Alberto Cougnet added fatty prosciutto to the mix (Cesari, p. 144).

Click on the image to zoom in and zoom out.

At first, people use cuts as fine as veal tenderloin. But in more recent years, most recipes rely on a combination of ground beef and freshly ground pork pancetta.

When Did People Start Deglazing the Meat with Wine?

Why add wine to dishes — and to ragù in particular? Professor Dario Bressanini explains:

“Alcohol helps dissolve certain flavor molecules that remain trapped in the meat and vegetables. On top of that, the aromatic components of the wine add depth to the ragù.”

(Bressanini, 2011)

Wine was already in use back in 1790, when Francesco Leonardi included it in his famous cookbook L’Apicio Moderno (Accademia Barilla, 2025).

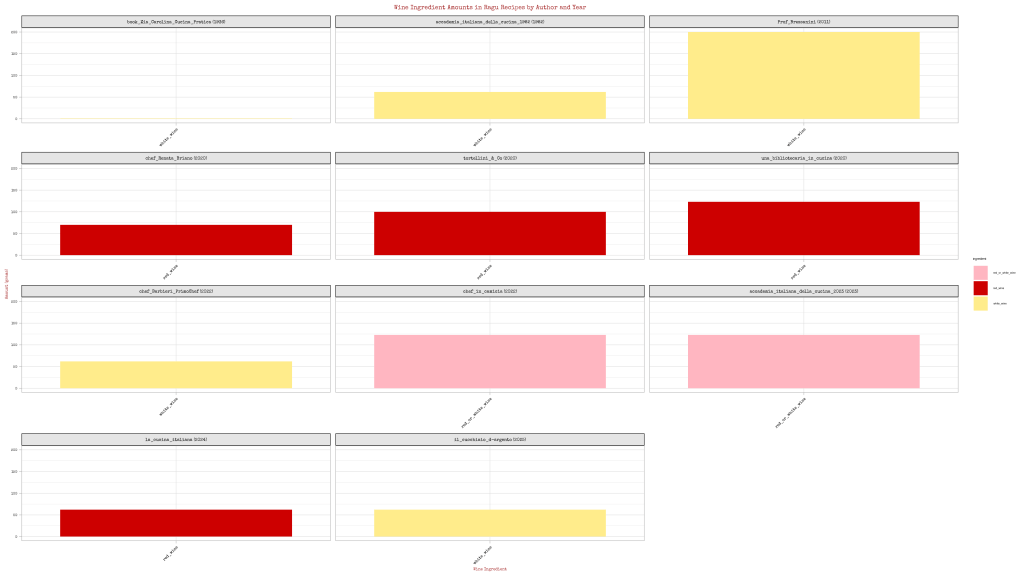

However, if you take a close look at the bar chart below, you’ll see that wine was listed only in 11 recipes out of 15 and disappeared from ragù recipes for several decades starting in the late 1800s. It reappears in a 1936 version. Why the pause?

Click on the image to zoom in and zoom out.

There is no clear explanation in the sources I found. But a bit of research points to a possible link: phylloxera, the vine disease that devastated European vineyards in the 19th century. According to Zulin from the University of Padua, vineyards across the continent were seriously affected by this pest, which the French called la bête (Zulin, 2025).

Add to that the First World War, which likely impoverished the Italian diet overall — including the possibility of using wine in cooking.

Ragù in Wartime

During World War II, ragù changed dramatically.

International sanctions against Italy had a serious impact on daily food supplies. The high cost of meat led to simpler recipes, most with little or no beef at all. Even the amount of fat was drastically reduced (Cesari, p. 152).

1982: Ragù alla Bolognese Becomes Official

Once you’ve found the perfect recipe, many would say, why mess with it?

And indeed, in 1982, the true recipe for ragù alla Bolognese was officially registered at the Bologna Chamber of Commerce (Cesari, p. 152).

The Italian Academy of Cuisine laid out the official version, the acceptable variations, and the heresies — the changes considered a crime.

THE Recipe (yes, with capital letters out of reverence):

- 400g coarsely ground beef

- 150g fresh pork pancetta (sliced)

- ½ onion (about 60g)

- 1 carrot (about 60g)

- 1 celery stalk (about 60g)

- 1 glass red or white wine

- 200g tomato purée

- 1 tbsp double-concentrated tomato paste

- 1 glass whole milk (optional)

- Light broth (meat or vegetable, cube is fine)

- 3 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

- Salt and pepper

ALLOWED VARIATIONS

- Mixed meats: beef (~60%) and pork (~40%) (loin or neck)

- Hand-chopped meat instead of ground

- Flat or rolled pancetta in place of fresh pancetta

- A hint of nutmeg

FORBIDDEN VARIATIONS

- Veal

- Smoked pancetta

- Only pork

- Garlic, rosemary, parsley, or any other herbs/spices

- Brandy (instead of wine)

- Flour (as a thickener)

YOU MAY ENRICH YOUR RAGÙ WITH

- Chicken liver, heart, and gizzards

- Crumbled pork sausage

- Blanched peas added at the end

- Soaked dried porcini mushrooms

(Source: Italian Academy of Cuisine – Official Recipe)

Note: the Italian Academy of Cuisine updated the recipe in 2023, therefore there are two entries in the dataset.

The Scientific Ragù

Among all the recipes analyzed, one stands out. It is a sort of scientific ragù, developed by Professor Dario Bressanini. It uses mostly the same ingredients as the others, but it includes a critical step: the Maillard reaction. It also incorporates ingredients like milk or cream — and explains why these additions improve the dish.

It is also my personal favorite, and the one I follow whenever I make ragù. You can find it here: Bressanini’s Almost-Bolognese Scientific Ragù (Bressanini, 2011).

Wine, Milk, Cream

In the official ragù alla Bolognese recipe from the Italian Academy of Cuisine, milk is listed as optional. But in his version, Professor Bressanini recommends having a full liter of it on hand. Why? Because milk adds fat to the sauce — and fat means flavor.

The same goes for cream, which is essentially a more concentrated form of milk. In Italy, cream can contain up to 35% fat, while milk only has around 4.5% (Bressanini, 2011).

Click on the image to zoom in and zoom out.

Conclusion

As this brief exploration into the history of ragù alla Bolognese shows, “it hasn’t always been made this way.” The keys ingredient were introduced gradually over time, until the recipe reached what we might call a small masterpiece of culinary balance.

In recent decades, most versions of ragù have aligned around the templates set by Artusi and the Academy. The flavor of Bolognese meat sauce is now precise and recognizable: both the cook and the diner know to expect meat, tomato, soffritto (carrot, celery, and onion), and wine. Introduce ingredients that are too bold and you lose the balance. One thing thar probably makes this recipe so perfect is that it has been optimized for serving with pasta.

The recipe is also a minor triumph of identity — and of engagement – from a marketing perspective. A single dish comes to represent Bologna, its traditions, and the care and quality that local cooks bring to their craft.

References

Accademia Barilla. (2025). L’APICIO MODERNO DI FRANCESCO LEONARDI. Academiabarilla.it. https://www.academiabarilla.it/biblioteca/lapicio-moderno-di-francesco-leonardi/

Bressanini, D. (2015). Le ricette scientifiche: il ragù alla (quasi) bolognese – Scienza in cucina – Blog – Le Scienze. Repubblica.it. https://bressanini-lescienze.blogautore.espresso.repubblica.it/2011/06/13/le-ricette-scientifiche-il-ragu-alla-quasi-bolognese/

Cesari, L. (2021). Storia della pasta in dieci piatti (Kindle, pp. 102–152). Il Saggiatore.

Parma e la sua storia. (2025). Teca Digitale Lazzari, Il piccolo focolare. Parmaelasuastoria.it. https://www.parmaelasuastoria.it/Lazzari-Il-piccolo-focolare.aspx

ZULIN, A. (2025). La devastazione della fillossera nell’Europa dell’800, e la nascita della “viticoltura moderna”.. Unipd.it. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12608/42952

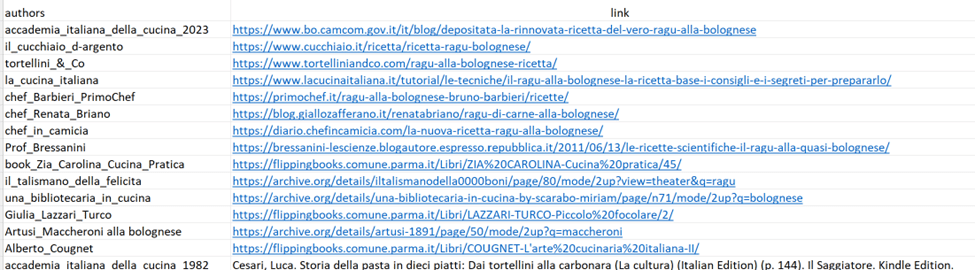

Authors and recipes used for data collection

Click on the image to zoom in and zoom out.

Follow me on Instagram:

Leave a reply to Nicole Phillips Cancel reply